Our Pentecost is Too Small

Photo by Vincent Guth on Unsplash

I was somewhat shocked at the public reaction to the recent total solar eclipse. News coverage showed large crowds gathered in stadiums, some people having driven hundreds of miles to view the spectacle. A friend of mine, who is a devout Christian, drove from Tennessee to Texas for the event. Afterward, he shared with me that the experience of viewing this total eclipse was among the top five spiritual experiences of his life. His story was not uncommon; Christians and non-Christians alike were captured with the wonder and awe of this magnificent event.

On the whole, I fear that many pastors and Christian leaders missed a grand opportunity to connect the eclipse with the good news of the Gospel. I dare say that there were few sermons on the Sunday preceding the eclipse that tied the wondrous creation passages found in the Bible to the solar wonder about to unfold.

Within the Charismatic-Pentecostal camp, there was the usual speculation regarding how the eclipse related to end-times prophecy and to recent events in Israel. Preachers and “prophets” added fuel to the already stoked-up fear that permeates these circles.

Those who were silent about the eclipse’s spiritual implications and those who went off the rails in prophecy revealed a marked inability to connect with the natural world in a way that faithfully joins creation and salvation history. For most people, Sunday morning worship had little to do with Monday’s solar wonder. In our modern era, the good news of the Gospel has become domesticated indoors and relegated to the private and spiritual realm. Lest any of the creation attempt to come to church, sanctuaries are darkened spaces with little outside light. The wonder of the stage has replaced the many wonders of creation.

The Overlooked Festival

Because of our limited capacity to join creation and salvation history, Pentecost 2024 will suffer the same subverted fate as Eclipse 2024—largely overlooked or theologically misunderstood. Our Pentecost is too small. It’s been trapped inside, domesticated, and tamed to fit our particular theological senses. In Protestant mainline churches it’s popular to emphasize Pentecost as a unifying power that reverses Babel, bringing all people into God’s grand embrace. Worship on Pentecost Sunday thus becomes a celebration of unity and diversity. There may be red vestments, but there’s little actual fire. When I’m in these spaces, I often think, “Pentecost is not a lukewarm soup in which everyone swims.” In Pentecostal and Charismatic circles, Pentecost is viewed as the means of Spirit-empowerment. When I’m in these circles I often think, “The grand festival Pentecost is not to be reduced to your spiritual energizing force.” In both Protestant mainline and Pentecostal Charismatic worship, the public, cosmic, and eschatological messages of Pentecost are lost.

In his recent volume, The Scandal of Pentecost: A Theology of the Public Church (T&T Clark, 2024), Wolfgang Vondey writes, “There exists a persistent stereotype of Pentecost as an extraordinary and unrepeatable event accentuated by miraculous charismatic manifestations that find little continuity in the subsequent history of Christianity” (7). For Vondey, Pentecost is an ongoing, public festival that continues the public ministry of Jesus. As public, this festival continues the scandal of Jesus’s ministry, especially the scandal of the cross.

To Vondey’s admonition that Pentecost is an ongoing and public festival, I would add that its public dimensions are also cosmic. It signals that everything must change, and that everything will change. It portends the Great Day of the Lord when all that can be shaken will be shaken. It’s big. Really big.

Enlarging our Vision of Pentecost

We Western Christians need to enlarge our vision of Pentecost. We live far beneath its significance, and in doing so, our witness is diminished. The recent solar eclipse revealed how contemporary people long for the wonder, the enchantment of a grand, mysterious, and frightening otherness that is beyond human control and rational understanding. The festival of Pentecost provides all these things.

Pentecost is historically related to Israel’s Festival of Shavuot (Feast of Weeks). It commemorates the giving of the law at Horeb. Pentecost also celebrates the wheat harvest. From its inception, this festival tied together creation and history. It was a grand festival, a time when people brought the firstfruits to the temple in Jerusalem. In doing so, they formed a procession of ox-drawn carts loaded down with baskets of the harvest. The horns of the oxen were laced with garlands of flowers, and they were accompanied by music and a festive parade. Shavuot is celebrated today by decorating synagogues with greenery and flowers. In some instances, a canopy of greenery covers the space where the scrolls are read.

Shavuot also celebrates the giving of the Torah at Horeb. It may seem strange to mix an event remembering the fire and thundering voice of God present at Horeb with wheat harvest. It’s not so strange, for Torah did not destroy creation; it made it fully alive. There’s a midrash saying that, in anticipation of the giving of the Torah, Horeb bloomed with flowers.

For the most part, Western churches have lost the connection of Shavuot to Pentecost. We like the color red, celebrating the fire present in the Upper Room. In the Eastern churches, Christians continue the connection to Shavuot. They do not see Pentecost as the birth of the church. It signifies the fulfillment of Christ’s mission and the beginning of the messianic age (see Shepherd of Hermas, Vision 2.4 [8].1). It’s the Great High Feast, one that “unifies the fires of Horeb—and the tongues of fire in the upper room—with the bounty of harvest” (Cheryl Bridges Johns, Re-enchanting the Text: Discovering the Bible as Sacred, Dangerous, and Mysterious [Baker Academic, 2023], 100). Pentecost in the East is a time in which churches and homes are decorated with greenery. Sometimes processions are made to fields where crops are blessed.

Another important distinction in the Orthodox tradition is how the message of the whole book of Joel (not just Joel 2:28-29) is integrated into Pentecost. During the all-night vigil—the Service of Kneeling Prayer—that precedes Pentecost Sunday, Joel’s calls for lament are enacted. God’s promises of creation’s restoration are re-visited, followed by God’s promise to pour out his Spirit on all flesh.

The Icon of Pentecost

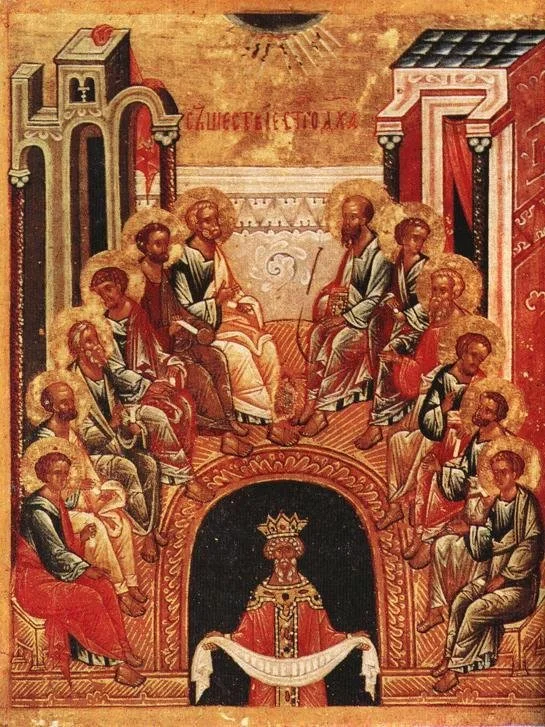

“The Descent of the Holy Spirit” (Source: WikiCommons)

The Icon of Pentecost conveys the larger, more creational and cosmic meaning of Pentecost. It depicts the outpouring of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles, who are seated in a semi-circle around the mythic figure of Cosmos. He is shown emerging from darkness, carrying a white cloth upon which sit twelve scrolls—the teachings of the Apostles. Cosmos is wearing a crown, and he visually represents the fallen order, tarnished, yet possessing a worn dignity. “The icon depicts a pneumatic cosmology, one in which there is a unified ethos of the spiritual and material worlds. In this image, heaven meets earth and the whole of the cosmos receives the light of the new creation” (Re-enchanting the Text, 102).

In his letter to the Colossians, Paul writes about the cosmic Christ, the one in whom “all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible…[A]ll things have been created through him and for him” (Col. 1:16). The coming of the Spirit at Pentecost is the grand re-claiming of all things. In this sense, the cross and the upper room are intimately and mysteriously related in a powerful and mysterious synergy.

The Cosmic Wonder of Pentecost

Pentecost celebrates the harvest found in the New Creation. It is heaven embracing earth, creating one grand, unified cosmology. In this space, creation is set free and begins to sing in harmony. In The Message, Eugene Peterson renders Colossians 1:20 as, “But all the broken and dislocated pieces of the universe—people and things, animals and atoms—get properly fixed and fit together in vibrant harmonies.”

Hildegard of Bingen’s understanding of cosmic harmony is helpful here. She saw that each element possessed “pristine sound that it had at the time of creation.” She wrote, “Fire has flames and sings in praise of God. Wind whistles a hymn to God as it fans the flames. And the human voice consists of words to sing paeans of praise. All creation is a single hymn of praise to God” (Analecta Sacra, vol. 8, ed. J.B. Pitra [Monte Cassino, 1882], 352). I have described the matter thusly: “At Pentecost, flames of fire joined with wind; these elements united with human voices in a single hymn of praise to God. Such a wonder had not occurred since the fall. In my Pentecostal imaginary, I see angels and heavenly beings joining themselves to this enchanted wonder” (Re-enchanting the Text, 105).

Last night, people around the world were astonished by the effects of a powerful solar storm. This storm, a level 5 geomagnetic on a five-point scale, created a spectacular display of color. In the U.S., the Northern Lights reached as far south as Florida. The skies over our Tennessee home shimmered with a rosy glow. We all rushed out to see the wonder.

Pentecost is a wonder, raining God’s glory down upon the earth. It has the capacity to burn away anything that cannot stand on the Day of the Lord, yet it brings verdant life to dead and dry places. It is creation set free. On Easter, we work hard to get people to come to church. Perhaps, on Pentecost, we should work hard to draw people outside, sharing with them the cosmic message of the restoration of all things.

I’ll end this essay with a testimony from over a century ago:

We pitched our tent near a place known as Albritton Mill…on the fifteenth of October and began to tell the people that Jesus is just the same, and the Lord is working with us confirming the Word with signs following…On Saturday night after a message was delivered, inspired by the Holy Ghost in obedience to the Spirit that reached the hearts of almost all the congregation of about 500, an altar call was made and there was about forty fell into the altar. The altar service had been going on for about a half hour, when the report was made under the tent that a large ball of fire was shedding its light on the side of the tent. The anxious crowd ran out from under the tent to see the wonder. The light passed upward, then fire began to pass through the elements as if it were raining fire, and great pillars of smoke would follow. It continued thus for an hour or so mingled with the cries of lost souls as the sounds of many waters filling the elements. As the fire and the smoke passed over several were saved and sanctified, while five were baptized with the Spirit. Glory to God. We are in the last Days…. (Personal testimony submitted by V. W. Kennedy, The Evening Light and the Church of God Evangel 1:18 [November 15, 1910]).

Cheryl Bridges Johns is Visiting Professor of Pentecostal Studies and Director of the Global Pentecostal House of Study at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio.