Ordered Grace for a Disordered Age: A “Benedict Option” for the Global Methodist Church

Photo by awelgraven

A Pastor’s Lament

A Methodist pastor I know recently wrote, “The churches I know about that I’d be willing to uproot my family for are Reformed Calvinist or Roman Catholic. I think there should be Wesleyan/Methodist churches that work like that.” As a retired military officer and Methodist pastor I am quite familiar with uprooting my family and I share his lament. The itinerant system of uprooting pastors for new appointments often feels quite random to pastors and churches alike. At the same time, as a Presiding Elder charged with being faithful to our open itinerancy, my initial response was less than enthusiastic. In that comment I heard what John Wesley might have considered prioritizing preference over obedience, and allowing one’s calling to become a career. As I reflected on his statement I began to see that perhaps behind his statement was lament and desire for a vision of robust Methodism. Contemporary Methodism has lost much of its depth and coherence. The pastor who made the comment above envisions a renewed form of Wesleyan life that can stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the best expressions of Reformed and Catholic Christianity. And before going any further I want to say: I’m with him in those thoughts.

Calvinist and Catholic communities tend to form believers through clear doctrine, disciplined structure, and visible order, whereas Methodist churches, in my experience, are often warm and active, but rarely match the depth of formation. To recover it, Methodism, as expressed in the newly formed Global Methodist Church, may need to adopt something akin to what author Rod Dreher called “The Benedict Option.” We need a strong rule of faith and life.

The Original Benedict Option

When Western civilization began to collapse in the fifth and sixth centuries, St. Benedict of Nursia (480–547) offered a simple but radical vision: communities of prayer and work (ora et labora), guided by a rule that bound life together in holiness, stability, and service. Benedictine monasteries became arks of faith, preserving not only theology but culture, learning, and community itself through centuries of upheaval.

Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option (2017) revived this idea for the modern era: in a post-Christian culture, the Church must again form intentional, disciplined communities to preserve the faith and raise up a countercultural witness. Such communities are not escapes from the world but schools of love, where virtue and vision are cultivated for the sake of the world.

Why Global Methodists Need a Benedict Option

At first glance, the Benedictine model might seem foreign to Methodist DNA—monastic vows, cloistered stability, and communal rule hardly fit Wesley’s itinerant, evangelical movement. But at a deeper level, while it may sound rather strange, I believe it is safe to say that Methodism has more in common with the Benedictine order than we may think. John Wesley’s Methodist societies in the 18th century were structured communities of disciplined discipleship:

Societies for corporate worship and instruction

Class meetings for accountability, mutual confession, and care

Bands for intimate fellowship and spiritual honesty

Rules of life governing prayer, fasting, giving, and service

Itinerant preachers who served as spiritual directors for lay disciples

Wesley called Methodism “a discipline ordained of God,” emphasizing that grace is not chaos but ordered energy or what we might call ordered grace. In today’s fragmented, distracted world, the Church needs that order again. A “Methodist Benedict Option” would not turn Methodists into monks, but revive the communal habits that make holiness sustainable by forming believers who can live faithfully amid cultural disorder.

The Triad of Traditions: Reformed, Catholic, and Wesleyan

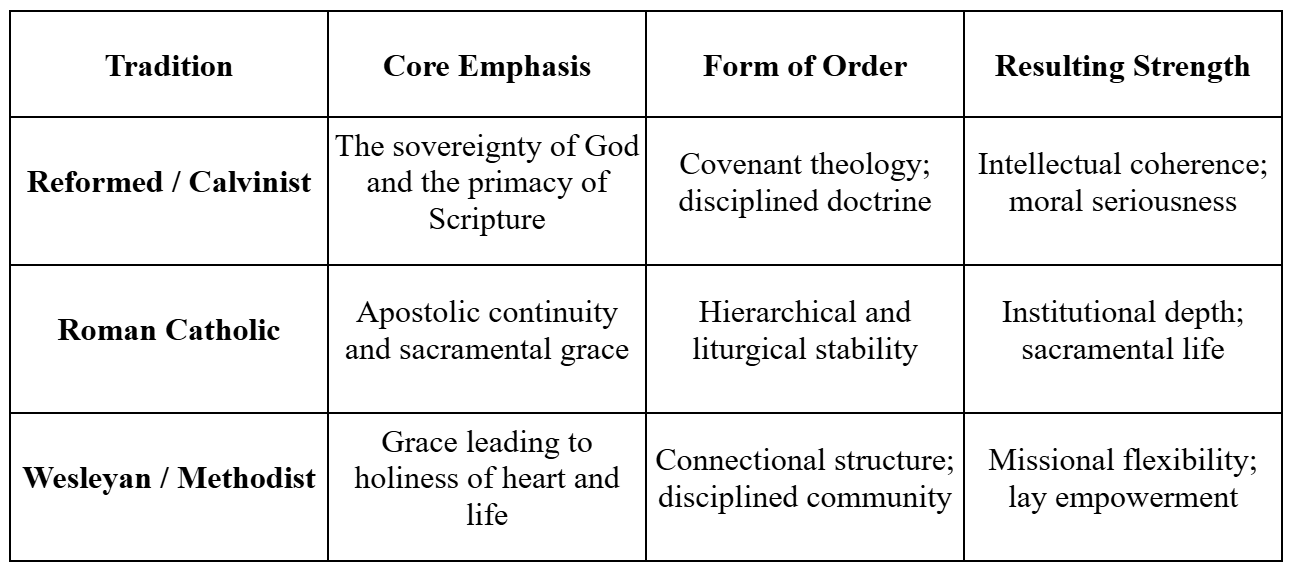

Each of the great Christian traditions offers a distinct model of order:

We are people growing together toward perfect love and these communities all emphasize belief, belonging, and becoming. But when Methodist structures of formation weakened, much of our distinctive ethos was lost. A Methodist Benedict option seeks to restore that balance: to make Wesleyan grace as formative and disciplined as Benedictine stability or Calvinist clarity.

What a Benedict Option Looks Like for the Global Methodist Church

A Rule of Grace

Churches should reclaim Wesley’s General Rules to“Do no harm. Do good. Attend upon all the ordinances of God,” not as slogans but as a living rule of life. Congregations covenant together around daily prayer, Scripture, fasting, and acts of mercy.Communities of Accountability

We must recover Wesleyan class and band meetings. We need smaller groups where we can watch over one another in love, confess sin, and practice mutual encouragement. These groups should become the backbone of discipleship, not optional programs.Catechetical and Theological Depth

Pastors and lay leaders must commit to systematic instruction in Scripture, doctrine, and moral theology. In a distracted age formation must be deliberate, not incidental.Liturgical and Sacramental Renewal

The early Methodists combined evangelical fervor with sacramental rhythm. We must recover frequent Communion, the Christian liturgical year, and daily prayer. Recovering Christian rhythm forms stability and sustains devotional zeal.Rooted Mission

Unlike monastic withdrawal, Wesleyan discipline leads outward. Methodism’s genius is its union of holiness and service, as Wesley said, “the world is my parish.” The leadership of a Benedictine Methodist community would stay in place long enough to transform it.

Ordered Grace in an Age of Disorder

St. Benedict taught that the monastery was a “school of the Lord’s service.” Wesley’s Methodism was a school of love, where ordinary believers were trained to live holy, joyful, and generous lives. What our time requires is not a new program, but a rediscovery of that school, a movement of ordered grace. The pastor’s longing for Methodist churches that “work like” Reformed and Catholic ones is not a wish to imitate their systems, but to recover that which once made Methodism so compelling. A Methodist Benedict Option calls us to:

Stability amid distraction.

Discipline amid drift.

Holiness amid confusion.

Grace amid all.

Such ordered grace produces not settled comfort but faithful readiness. Wesley did not form disciples who asked first where they wished to serve, but those prepared to go where Christ sent them. Obedience, not preference, was the governing posture. Yet this obedience was never rootless. When sent, Methodists stayed long enough to form holy communities marked by stability, discipline, and shared life.

The Church’s task, then, is not to help leaders find the place that suits them best, but to form leaders capable of faithful presence, ready and willing to go wherever they are sent. This is ordered grace in practice: obedience shaped by discipline, stability forged through community, and mission sustained by love rather than preference. It is not a strategy for clergy placement, but a way of life. And it remains the enduring genius of the Wesleyan way.

Neville S. Vanderburg is the pastor of Moore Memorial and Bethlehem Methodist Churches. He also serves as the Presiding Elder of the Grenada District of the Mississippi-West Tennessee Conference of the Global Methodist Church.