Real Renewal – What Does It Take?

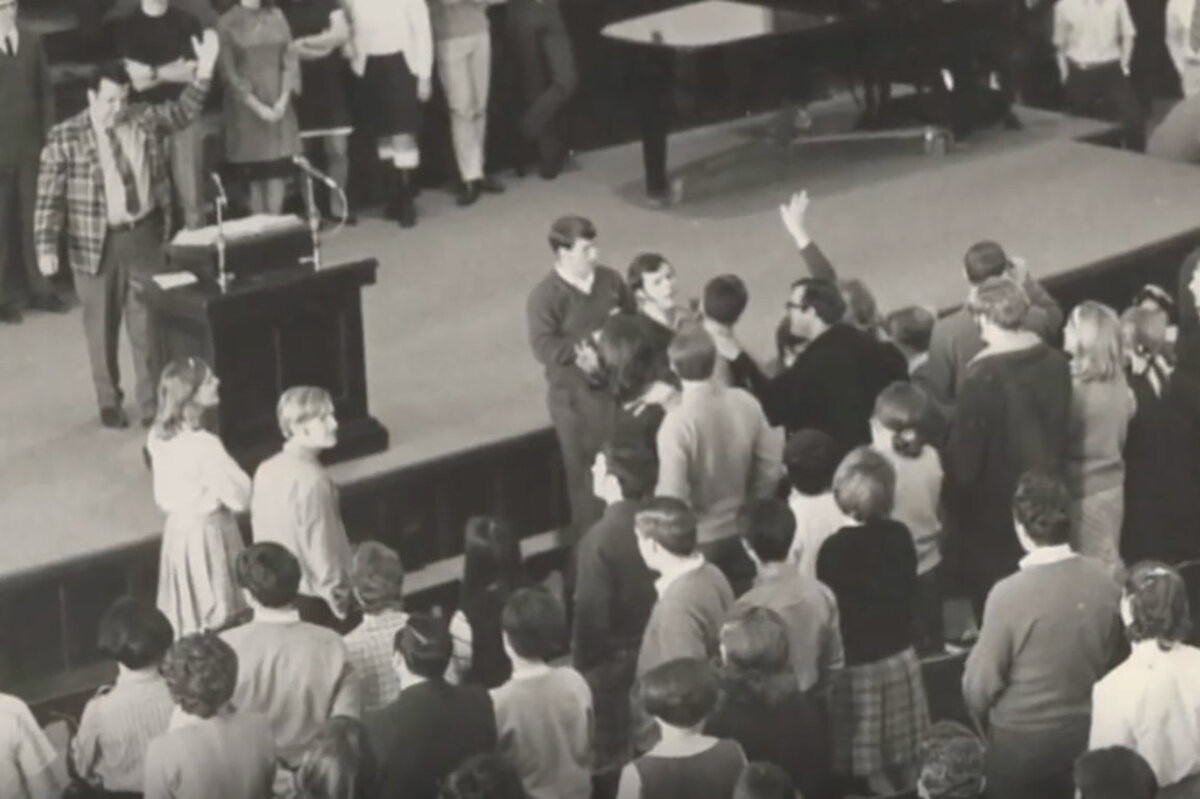

Asbury University students respond during revival. (1970)

I entered United Methodist ministry as part of a cadre of young evangelicals thinking that God would use us to revive The United Methodist Church. We didn’t. I’m not saying, of course, that our efforts did not count toward renewal (they have), but our vision has not come to pass. After almost four decades of ordained ministry, in which I have thought almost daily about and worked for renewal (a word I will use interchangeably with revival), I think I may be beginning to learn. Here are a couple of lessons.

Our glorious heritage is a real blessing, but also a potential pitfall. Because so many of the stories of renewal are so dramatic, we easily fall for associating them only with big events and seasons. It’s not really revival, we think, unless and until we see these big things happening. To be sure, I love the accounts of these seasons of renewal and have no doubt they are manifestations of God’s power. The Asbury College revival of 1970 played a significant part in my responding to Christ as a teenager. I have read and re-read One Divine Moment. I have watched the grainy YouTube videos and wept tears of gratitude in recalling how a team of Asbury students came through the little Kansas town where I was living and shared with students at our local Wesleyan College. They in turn reached out to some of us high school kids and brought us into that incendiary fellowship, as Elton Trueblood put it long ago. Along with a lay witness mission two years later, this experience set the course of my life.

An early example of the glorious heritage from John Wesley’s journal (one of many) from April 26, 1739, describes the operations we commonly recognize as revival:

While I was preaching at Newgate [near Bristol] on these words, ‘He that believeth hath everlasting life,’ I was sensibly led, without any previous design, to declare strongly and explicitly that God ‘willeth all men to be thus saved’ and to pray that if this were not the truth of God, he would not suffer the blind to go out of the way; but if it were, he would bear witness to his Word. Immediately one and another and another sunk to the earth: they dropped on every side as thunderstruck. One of them cried aloud. We besought God in her behalf, and he turned her heaviness into joy.

I have pondered these accounts many times, asking, “Apart from God’s freedom to act when and how he chooses, what made these moments so propitious? What underlying conditions provided the fertile ground for these plantings of the Lord?” We can see at least four, three of which people who have experienced revival know already, but bear repeating. The other, which has to do with cultural context, is less clear to us, but on reflection is especially enlightening.

For starters, although it does happen that conversion and renewal for some people seem to come out of nowhere without any (or much) prior soul-searching, more commonly people are ripe for transformation when they know their hearts and recognize their need. They know their true condition and understand that only God can deliver them. This is, in large part, what Wesley meant by repentance. It is accompanied, secondly, by humble transparency. A penitent sinner hungry for God and for a changed heart willingly sheds the fig leaf of self-sufficiency and lets her or his need be known to others. They want God more than they want to keep their self-respect. Third, in some cases, the Gospel preacher senses, as Mr. Wesley did in this example, that the Spirit is leading the message in a different direction than the one planned to apply the converting word to hearers’ hearts. This responsiveness is born of much prayer, both by the preacher and by all those, lay or clergy, who have prayed long and hard for revival.

In studying revivals in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—and even well up into the sixties and, perhaps seventies, of the twentieth century—there is another factor, a cultural one, that bears consideration. In one sense it, too, is well-known, but from another angle I don’t think we have understood its impact as well as we should. The people who responded to the Gospel so strongly in those earlier generations were also already sufficiently Christianized that they recognized their accountability to God as Righteous Judge. They believed in heaven and hell and knew that they did not measure up to a holy God’s assessment. We know that our culture is post-Christian. We cannot depend on background knowledge and beliefs that earlier generations had.

This fact, people already know. Where we need more awareness—and probably a good dose of honesty—is just how much a post-Christian culture has permeated our evangelical and orthodox congregations. Many people in evangelical churches have soaked up badly inadequate ideas about God, leaning heavily on all the positive angles that we use to prop up shaky emotional states. We in leadership roles have also succumbed to the same pressures, putting the Gospel in palatable terms. Our people generally have been insufficiently taught the whole counsel of God. People in evangelical congregations need to receive the sort of teaching that helps them see God as not only Comforter and Protector, but also Judge and Sovereign. We need to risk sounding judgmental once again.

Therefore, a big help to revival now would be to deploy the teaching role more robustly than we often do when we make plans for revival services. In the same section of John Wesley’s journal from which I earlier quoted, we find glimpses of this crucial aspect. Here are samples:

Thursday, April 5, 1739 – At five in the evening I began at a society in Castle Street [Bristol] expounding [emphasis added] the Epistle to the Romans; and the next evening, at a society in Gloucester Lane, the First Epistle of St. John. On Saturday evening at Weavers’ Hall also I begun [sic] expounding the Epistle to the Romans and declared that gospel to all which is “the power of God unto salvation to everyone that believeth.”

Sunday, April 15, 1739 – I explained [emphasis added] at seven, to five or six thousand persons, the story of the Pharisee and the publican. (In most respects this scene looks like a typical preaching moment in the Methodist revival, yet Wesley explains a text. This is a matter of style, certainly, but also substance.)

Tuesday, April 17, 1739 – I went to Baldwin Street and expounded, as it came in course, the fourth chapter of the Acts.

This third entry is especially interesting. Wesley was using the Book of Common Prayer’s daily scripture readings. On this day, Acts 4 was listed, hence his reference to “as it came in course.” When we look at the revival as it broke out in and around Bristol in those early days, teaching and exposition interweaves with moments of outpouring. Both are needed for sustained revival.

From examples like these, I hazard two thoughts about revival for our day that we need to put to work. First, teasing out from that reference to the Book of Common Prayer and remembering that the Wesleys daily combined traditional church disciplines (and demanded their people do the same) with dramatic charismatic manifestations, we need to grasp that sustained renewal will look more “Catholic” than many of us imagine or our comfort zones will tolerate. The capital “C” refers to those “high church” (ergo “Catholic”) practices often believed to be inimical to renewal. We can use the church’s liturgies in mindlessly rote ways, yes, but this is no reason to dump them. They are not the problem. Because they are a means of grace, they are also an avenue for revival. We make the mistake (I did) of identifying forms with formalism, which sets us up to read John and Charles Wesley and our tradition wrongly. Spontaneity and the freedom of the Spirit go best with the tested, doctrinally sound liturgies of the church across the centuries. There is enough variety in the tradition to keep us “fresh.” Becoming more “Catholic,” in this sense, while yearning for and depending upon the Spirit’s dramatic operations is the way of real renewal. I’ve changed my tune considerably on this point since I was a young man hot for revival.

Real renewal also will look more “scholarly,” even “academic,” than many of us imagine. I use these terms quite intentionally. We must not leave what is thought of as academic work only to the professional academicians. Along with fervent and focused preaching, we need good teaching, hence the examples of John Wesley’s expounding and explaining in the course of his revival preaching. Try to imagine him engaging in this activity. It helps to read his sermons in this light. They bear the marks of careful and systematic thought – of description and explanation and argument – very much like what scholars do. It is especially important for us to understand the scholarly dimension of pastoring and preaching. For renewal, we need more teaching, not only of the practical kind (e.g., how to steward resources and families well), but also of the explicitly theological kind (why it matters that we recognize God as Trinity and why we reject modalism). Renewal requires a level of commitment to study that—let’s be honest—only a tiny slice of American Christians show interest in trying. We need to study! Yes, knowledge puffs up while love builds up, yet study—shot through with humble prayer—is a means of grace that the Spirit uses to renew the heart.

Another example from history that feeds our heritage: German Pietism, led by Philipp Jakob Spener (d. 1705), was structured around small groups—collegia pietatis—for scripture study and application as well as prayer and mutual support. We know this small group practice well, but we may not sufficiently recognize that, along with prayer and mutual encouragement, went study. Were they sitting in a classroom listening to a lecturer drone on about minutiae? Of course not. They read Holy Scripture together and soaked themselves in it—and in sermons and other writings by Pietist leaders—and strove to do what they sensed God telling them to do through their study. This is what I mean by a more scholarly or academic dimension of revival. In a recent blog post I drew a sketch of how study has played a central role in the faith from the very beginning. For real and sustained renewal, we need to reclaim study. Along with all the other aspects of revival, it must climb in our list of priorities.

The trajectory of these thoughts blur the lines, I realize, between evangelism and revival. I don’t know how to sort out the differences very well and, in the end, I’m not sure it’s necessary. Revival and evangelism have always overlapped. The saints need renewing. Many church members need evangelizing. What I have tried to lay out in this little essay is badly needed in both arenas. While we seek the renewal of the heart, may we wait actively, employing all the means of grace—but especially now, of study and liturgy—that God has placed at our disposal.

Stephen Rankin is a member of the North Texas Annual Conference and founding director of Spiritual Maturity Project.